Wooden Pillow

MacGillivray, Narrative I 286

Solo Canoer

MacGillivray, Narrative I 294

Hair Style, Papuan Fashion

New Guinea September 1849MacGillivray, Narrative I 298

We anchored after all last night, but in a spot pretty exposed to all the swell and about a mile and a half from the Bramble which is close in shore.

The latter has been playing off some brilliant achievements since we parted company. I carefully gathered the following particulars from three of her officers. On the 31st of last month, she was standing along shore as usual when it fell calm and many canoes came off. Their number gradually increased until there were not fewer than sixty surrounding her and as they usually contain seven or eight men there were probably not fewer than four hundred natives present. This was altogether too many to be pleasant, as their apparent strength might have induced the niggers to attempt an attack, though they would have been wofully astonished when the grape began to tear holes among them.

Yule beat to quarter and made every preparation but no attempt was made and a breeze springing up let him off with a fright.

On the following day, the Bramble had as I understood anchored opposite some spot further down the coast (I am sure as to her being at anchor) when a canoe came off, unarmed but without having any article for barter on board. One of the Brumer Islanders was recognized by Moss as an old friend; Yule's permission was asked to have him on board, which was granted; and he brought up with him a friend to whom he wished to show the wonders with which he was familiar.

In the meanwhile three canoes joined the one already alongside, all perfectly friendly, and all, to all appearances, unarmed. Nine or ten others were seen inshore, at a very considerable distance, apparently coming to the ship.

Suddenly Yule came up and ordered the native down into his canoe and then waived to all the four to be off. They did not quite understand all this and hung on astern making their usual friendly signs. Yule then became excited and called for his gun, which was loaded with small shot. He waived to the natives again to be off and called out "Now I give you fair warning, I give you fair warning", and finally fired right among them. So little did the natives understand him, that while some looked astonished others laughed as though it had been something done for their amusement. Yule hereupon fired again and at first (so excited was he) snapped his already fired barrel, complaining that the cap would not go off. This time there was no mistake, the natives felt that if a joke it was a very queer one, looked one moment as if in utter astonishment (so my informant described it) then seized their paddles and paddled away as if the devils were behind them. One man took up water in the palm of his hand and cast it towards the Bramble as if "casting the dust from off his feet" at such a treacherous set. Not content with this Yule ordered one of the marines to take his musket and fire close to the unfortunate devils. The man obeyed and the bullet dropped within a few yards of the canoe. The gallant lieutenant then ordered another to fire close to but not to hit the canoe. This man is a great blackguard and as I was told took deliberate aim with every appearance of intending to fire in earnest, and as it turned out the bullet passed under the outrigger. After that this gallant and humane commander "piped down", and wrote a long despatch about the "engagement" to Capt. Stanley.

Suppose we landed at a village, the natives received us with every appearance of friendship, took one or two of our number up to their houses, and then as we were shoving off treated us to a shower of spears? What should we say? When should we have held forth aufliciently about their treachery?

And yet some day or other a big book will appear with a statement to the effect that "every effort was made to conciliate the natives and treat them kindly."

The most remarkable occurrence that has yet befallen us happened yesterday. A large party of natives came on from the islands and shortly after their arrival Scott (the Capt's Coxn) and several seamen wandering about fell in with a party of them–gins–among whom was a white woman disfigured by dirt and the effect of the sun on her almost uncovered body; her face was nevertheless clean enough, and before the men had time to recover from their astonishment she advanced towards them and in hesitating broken language cried "I am a Christian–I am ashamed". The men immediately escorted her down to Heath's party, ashore watering, who of course immediately took her under their protection, and the cutter arriving very shortly to take the party on board, she found herself once more safe among her own people. Three natives accompanied her off in the canoe whom she called her brothers and who appeared much interested in her.

This is her story, told in half Scotch, half native dialect, for she has been so long among these people as nearly to forget her mother tongue.

Her name is Thompson and her maiden name was Crawford. She was born in Aberdeen and her father was a tinsmith who emigrated when she was about eight years old to Australia. From her account he appears to have been at first in very good business in Sydney but latterly became unsteady and consequently descending lower in the scale, was, when she left him, only a journeyman.

When between fifteen and sixteen she left her father's house without his knowledge or consent and making her way up to Moreton Bay with a lover of hers was there married to him. She wrote to her father to tell him that she was happy and doing well but has never since heard anything of him. The husband was a sailor and appears to have been a very handy sort of man, according to her account he could make everything for himself from the shoes on his feet to the hat on his head and furthermore fitted up very well a small cutter rather larger than our Asp.

She tells me he was a great favourite with Capt. Wickham and might have done very well at Moreton Bay. However the tempter came, in the shape of an old sailor who had been wrecked in a large ship, well laden, on an island in Torres Straits, and he gave Thompson such brilliant ideas of the profit to be obtained by any one who should take the trouble to visit the wreck and walk off with "jetsam and flotsam" that the latter resolved to go in his cutter and either return to Moreton Bay or go on to Port Essington (at which place he seems to have had some idea of settling). About this time Dr Leichhardt was starting on his overland expedition and it appears that he wished Thompson to join him, but the latter, the worse for him, preferred his own exploration, only promising on his arrival at Port Essington to inform the people of the coming expedition and induce them to send a party to meet it.

After living, then, about 18 months at Brisbane, Thompson with his wife and three men, started in the cutter on their ill-omened journey. They had nearly reached the desired island when a heavy squall came on, and their little vessel was utterly wrecked upon a reef running out from the island.

Two native canoes which were out turtle-fishing were similarly distressed by the squall but the natives easily reached the shore. Not so with the unfortunate tenants of the cutter: the three men were drowned, and Mrs. Thompson was drowning when one of the blackfellows (Aliki who came on board with her) swam out, and seizing her arm brought her safely to land. [It was not Aliki but Toma-gogi who swam out. Aliki only assisted in helping her on board the canoe. (Note, added later.)]

They treated her very kindly, fed her and protected her from insult. One of the old chiefs, who had lately lost a daughter, persisted, according to their common belief that white people are the ghosts of black, that she was this very daughter "jump alive again" and she seems to have been regularly adopted among them, so that she talks of her brothers, nephews etc. Years rolled on, and by degrees she approximated towards her friends, adopting their language so that she speaks it fluently and at present evidently thinks in it, having in talking to you to translate her native thoughts into plain English, sometimes a matter of considerable difficulty, and at the same time adopting their ways so that her manners present a most ludicrous graft of the gin upon the white woman.

For the first twelvemonth she kept some account of time but afterwards lost it, so that she has no idea of dates at present, and indeed, as she says herself she would have forgotten her own language had she not been accustomed to sing to herself at night all the old fragments of songs and ballads she could remember.

The natives appear to have treated her quite as a pet; she never shared in the labours of the women but stayed in the camp to look after the children while they went out on "hospitable cares intent". Of the kindness and good disposition of the men she speaks in the highest terms, and of the women too she speaks well but says that some of them were not so kind.

Year after year she saw the English ships sail by on their way to China but never had any opportunity of communicating with them, and sometimes she says she was very sorrowful and despairing.

Last year she knew of our being here but the natives would not let her come, and when the canoes were setting out from the islands to visit us for the purpose of getting tobacco etc. the women were very unwilling to let her come, and it was only partly by promises to return, partly by the influence of "Toma-gogi", one of her brothers, a gentleman about 6 ft. 2 and doubtless proportionately respected, that she got away.

So far as we can judge she has been five years among these people, and is therefore even now a very young woman; and indeed notwithstanding the hard life she must have led, she looks young, and I have no doubt when she is appropriately dressed, and gets rid of her inflamed eyes, she will be not bad-looking.

Poor creature! we have all great compassion for her and I am sure there is no one who would not do anything to make her comfortable. Capt. Stanley gives her his workshop for a cabin, and as soon as she recovers herself sufficiently to understand the use of a needle, she can have as much calico and flannel as she wants, to make mysterious feminine toggery.

She must be content to take a long cruise with us, but it will be at any rate, I should think, preferable to her late circumstances.

I inquired of her if she knew anything about poor Kennedy's murder; she told me that "Baki" (an old friend of ours) had told her all about it; that the people here had nothing to do with it, but a bad tribe to the southward; and that they killed him for nothing but his clothes.

It appears from further inquiry that Mrs Thompson was wrecked on Possession Island and that the natives carried her over to the Southern Prince of Wales Island, where she subsequently lived. And until we arrived she never left the Prince of Wales Islands. Curiously enough the complete identification of the island on which she lived was afforded by the fact that as she stated, on one point there was a cairn or heap of stones which the natives told her had been built by the white men. Now Mr Yule had built a cairn in the very position she indicated, some four or five years ago.

She has already given us a great deal of curious information about the habits of these people, with an air of the most perfect truth and sincerity, and no little intelligence. One story was rather startling. She says that a little to the N. and W. of us there is a tribe of very bad natives, and that one night they lighted a very large fire on their beach as a challenge to the P. of Wales Id. blacks, to come over and fight them. Her friends, no wise backward, lighted a fire on their side to show that the challenge had been accepted, and one night embarking all their disposable force in six canoes landed very secretly on the main. They stole up to an encampment of their enemies and falling upon them suddenly killed two men, a woman and a child. They cut off the heads of these and returned in great triumph, making a hideous noise upon a conch, to the island. A great corobbory was celebrated and the four heads having been placed on one of their rude ovens they ate the eyes and pieces of the cheeks of their enemies "to make them brave" as they said.

The women were excluded from all share in this recherché repast.

We asked if the mainlanders made no reprisals, but it appears that they had no canoes. However, our friends were not altogether secure, for some natives from the northward landed secretly on the island on one occasion and cut off the heads of a man and an old woman with which they decamped. The fellows have a special apparatus for cutting and carrying heads, consisting of a bamboo knife with a long loop. They do not make this, any more than their arrows, but get them from the natives to the northward.

Mrs Thompson gives us a rather unfavourable idea of the morals of these people. She says that they have no idea of a Supreme Being and that they always laughed at her if she talked of anything of the kind. But they believe in all sorts of varieties of ghosts. When the heavy squall of these latitudes gathers and the clouds topple over one another in huge fantastic masses they say the "marki" (ghosts) are looking out for turtle and they profess that one comes down and fetches a supply for the rest. So again they believe that porpoises and sharks are a sort of enchanted beings and they never injure them.

The natives have no idea of moral or legal obligation. No fixed punishments are annexed to any crimes. Theft usually produces a scolding match between the aggressor and the aggrieved, in which the filthiest language is made use of. Murder she told us never occurred (among members of the same tribe) to her knowledge, and the men never use personal violence to one another although the women do. Unchastity before marriage is thought nothing of. Afterwards, its punishment depends pretty much upon the temper of the husband. He would be considered quite justified, however, in spearing both parties if taken flagrante delicto. Otherwise Mrs. T. very naively told us that the husband's wrath would be very likely regulated by the state of the quisdilli [?]. If that were kept full of yams he would probably shut his eyes. It is astonishing how similar man is to man from "China to Peru". Child-murder prevails to the most fearful extent. All illegitimate children are destroyed by burying them in a hole in the sand immediately on their birth unless the father intends to marry the girl, when he can if he likes order the offspring to be saved. The children of the married owe their life entirely to the caprice of the husband. If he says they are to live, they live. If he orders them to die, they are all buried at once. It is very common for a man to order all his male children to be kept and all the females to be killed and Mrs T. gave us by name several natives whom she knew to have destroyed child after child.

The mothers pay their children very little attention and take care to see "their own bellies filled first". The old and infirm share the fate of the children and live altogether par hasard.

The affections appear to be at the very lowest ebb–worse than on board ship.

A man's importance and the number of his wives go together; they have sometimes as many as five, but the first and last are the only recognized wives, the others appearing more in the light of concubines. Girls are married as early as 10-11 years of age.

Two great occasions occur in the course of a man's existence –his induction to the privilege of manhood (assuming the toga virilis one might call it if they had any pretence for a toga at all) and his burial. The women have no observances of the former kind, and unless they happen to be young and favourite gins, are very often tossed into a hole without ceremony.

When a man dies the whole camp goes into mourning, men, boys and women smear themselves with clay and casting themselves down with great lamentation pass the time in mourning. In the meanwhile the corpse is straightened and the eyes closed and it is placed upon a sort of bier formed of two long poles with a number of cross-sticks placed on them, bark is placed over the body and the whole bound together into a secure mummy-like package. On the afternoon of the day succeeding the death two men take the corpse on the bier and convey it to some already appointed place where it is set upon a sort of trestle formed by two poles crossing one another and supporting the bier, at each end. Here it is left, but the mourning continues for a month or six weeks and no corroborrys are held in the camp. By this time the head of the corpse has usually rotted very nearly off and when this is the case a day is appointed for its removal.

December 3, 1849

Left Cape York

Anchored the same day about 3 P.M. under Mount Ernest Id. or Tragé.

In the afternoon a boat sent ashore with a party to land on the island and I took the opportunity of going. As we approached in the ship we had seen three or four natives sitting on a sandy beach near a long hut but some of them were women and had disappeared before we landed.

We saw only one oldish man, standing at the edge of the brush which bounds the flat plain on which you land, on one side, and he did not seem very desirous to have anything to do with us. However we gathered branches and shouting Poud! Poud! Colaiga! etc. at the top of our voices we contrived to get near enough to scratch hands, an operation which the old gentleman performed with great energy, giving you three distinct tugs. We went through the usual formalities of inquiring one another's names etc. and gradually established a friendly footing. The old man made great inquiries for "Sagouba", "Tooree", "Aga", "Taparra" etc., offering tortoiseshell in exchange, but we had nothing but biscuit with us. We gave him plenty and soon set him in good humour. He was greatly alarmed at first hearing the noise of the guns, but being shown that we only killed "Worroi" he became reassured and at our request readily conducted us to the village.

On our way thither we had a peep at what looked like a very singular inclosure but our guide did not wish us to go nearer, making signs that it was a place to be feared. The houses are enclosed in a low fence of bamboo about five feet high, and are built of square or penthouse-shaped frames not higher, and thatched with coarse grass. They are a sort of combination of the Darnley Id. fence with the Cape York hut.

One or two cocoa-nut trees were growing near the huts. The trunk of one was ornamented with red paint. On our wishing to procure some of the tempting green cocoa-nuts our friend gave us to understand that the tree belonged to some other person (whom he named) and that therefore "his legs were sore" and he could not climb to get them. However if we would bring plenty of "Aga" and "Tooree" tomorrow we could have as many as we liked.

The cooking places were on little low stages before the huts.

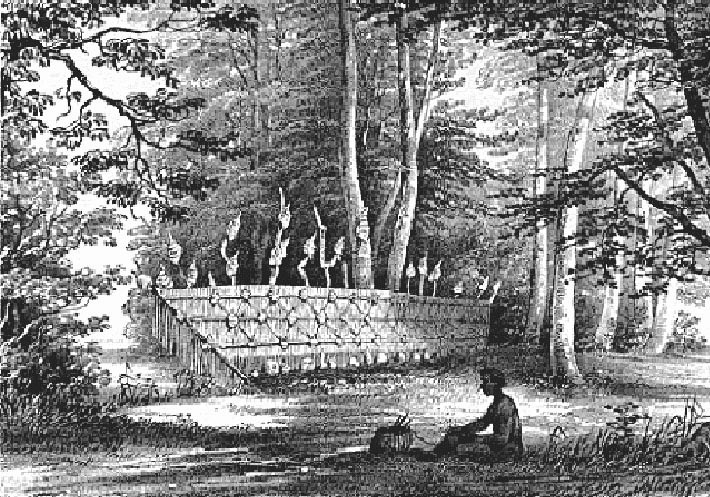

Seeing a native path leading into the brush I began poking my nose into it and as the brush looked pretty we proposed to our guide to take us by it. He willingly acceded and passing through a low arched opening, we came at once into a most beautiful opening in the brush arched over by magnificent trees and so shaded and cool, with such a "dim religious light" pervading it, that it looked quite like a chapel, and indeed the name would not be wholly inappropriate, for there was a strange fantastic sort of monument in this savage sanctuary. Suppose a great screen of posts five or six feet high supporting vertically a long wall-like plaited mat, cut at each end so that the upper ends overhung the lower, and their ends fringed with long hanging strips of grass. The tops and offshoots of the posts were covered with huge reddened Fusus shells. The front of the screen was set with regular series of the spider shell, also reddened, and stuck up against the foot of the screen were a number of flat stones of all shapes carved and painted with hideous human faces.

Panooda (that was our friend's name) gave us to understand that this was a sort of tomb and he named to us some half a dozen individuals whose effigies were depicted upon the stones. Panooda plainly considered the thing a considerable work of art and was considerably pleased by our sketching it. After a little while, seeing that we were good peaceable folks, he let us go up close and handle this redoubtable affair. He was greatly amused at our looking to see if there were anything behind the screen, and very soon lost all the awe with which he had at first affected that the place inspired him.

Panooda subsequently took us to a native well, to plantations of yams and tobacco (exactly resembling those I had seen at Double Id.), and to a very singular grave of which I hope to see more tomorrow. By canoe off to the ship at sunset.

Brierly and I spent the greater part of yesterday on the island, on a regular sketching expedition. Old Panooda was down at the beach before we landed, according to appointment, and had brought with him some tortoiseshell and a cocoa-nut wh. he offered to us. Capt. Stanley gave him a knife with wh. he seemed much delighted, but nevertheless he attached himself to us as if he considered himself our regular "cotaiga".

We waited until the skipper had got sights as he wanted to see the wonders, and then visited the houses, the "Wowres" and the plantation, after which to our great relief the little man took his departure and then we and our cotaiga went and sat down in the beautiful "chapel", studying lights and shades in most artistic fashion, as we proceeded with our drawings. Panooda would occasionally request a look and then with a grin of satisfaction and a sort of grunt relapse into a most patiently quiescent state. He was a first-rate fellow in this respect, never fidgetting or bothering us for biscuit or sagouba, but where we were he seemed content to be and he was grateful for all he got, great or small.

There we sat like three Chinese Josses squatted down. We knew the hot sun was pouring down a flood of light and heat outside–the chirp-chirping of the cicadas and the glare of the sand at the end of the long avenues told us that–how it enhanced the coolness of that dim green shade! The silence and the gloom heightened the strange appearance of the fantastic savage monument. You might have fancied it a temple for the performance of strange and horrible savage rites, had it not looked so utterly peaceful. Now and then a stray pigeon would perch over our heads, or a pair of the beautiful ground-doves would begin their soft cooing, or a pair of ant-thrushes would be heard answering one another's loud calls from either side of the wood.

I shall never forget the beauty of the place; while in it I felt as if listening to beautiful music.

When we had finished our sketches and measurements we migrated over to the other "wowre", which though not so beautifully placed is prettier in its structure as there is a sort of Gothic arch formed by two high crossing poles in its centre. Instead of being made of grass thatch too, it is formed of cocoa-nut leaves plaited together.

After this we bethought ourselves of the corporeal man and descended to lunching, and under the influence of the meal we "snaked" old Panooda into taking us to see his wife and children who were hidden away in the bush. Why he consented was curious.

The Goodangarkagi (Cape York) blacks had called Brierly "Antarke", believing him to be the "marki" or ghost of a Mount Ernest man of that name who had lately died. Now it so happened that Panooda had taken to wife a certain daughter of Antarke's, Domani by name, and when this came out in the course of conversation Brierly thought it would be a capital pretext for seeing the woman, and gravely tried the pathetic with Panooda, insisting that it would be very unkind not to let a father see his daughter and grandchildren. Panooda admitted the plea fully but still hesitated, when the scale was turned by my giving him a piece of finely variagated and marbled paper out of my drawing book, while Brierly promised Domani a shirt. He came to us very confidentially and told us that he had no objection to take us two but we must have no "kalaki" or guns and on no account must any of the other "markis" know anything about the matter. Of course we agreed and off we started. He took us right away into the bush for some distance off the native tracks and then told us to sit down while he went away. We sat very patiently for about half an hour, occasionally speculating on our foolish looks if he did not come back, till at last we saw him return. He made signs to us to be quiet and led us up the side of the hill for a short distance, where we came upon his family seated ready to receive us under the trees. There was the wife Domani, a good-looking clean native with a child at the breast; "Dowai", a pretty grown-up daughter; and a third younger child, also a daughter. Poor Domani had the "dopo" or ague. A most friendly recognition took place between Brierly and his daughter, we were all introduced to one another and then commenced a great palaver. Everything was new and delightful to them, and Dowai gave me a most enchanting smile in return for another piece of marbled paper and was not a little vain when I made a sketch of her. I was much pleased with the cheerful quiet ways of these people and most agreeably surprised at the contrast they presented to the Goodangarkagis in point of cleanliness. After half an hour's chat we departed, "scratching hands'' very cordially.

On the way back we passed some yam and tobacco plantations more extensive than we had hitherto seen. Some of the yam plantations had their stakes united by horizontal cross-bars of bamboo and some had fish-shaped red smeared scarecrows suspended in them,which turned and twisted in the wind. There were eight of these plantations, each containing on an average 30 yam plants, covering a space of about 1/4 acre.

Panooda explained to us that they belonged to 18 people, counting them up by name first on his fingers, and then on the wrist, arm and shoulder joints and top of the head. (Brady told me in the evening that he had seen a great deal more cultivated ground.)

We went back to the well and drank with avidity out of an extemporaneous leaf cup some most filthy water, and then betook ourselves to the ten-skull grave. This was very curious. In a little recess of the brush close to the beach was a tri[a]ngular heap of turtle and dugong skulls lying nearly East and W., the pointed end being westward. At this end there was a flat stone placed vertically; at the other end or base of the triangle ther were two stones, one at each corner, and supported upon them a flat board (apparently from a wreck) on which were arranged ten whitened and weather-worn skulls. At each end three little turtle heads were placed under the end of the board. In front of the skulls lay a flattened-conical big stone painted with red and black, and white feathers stuck around it. At one end of the skull board there was a long thin stick with three large fruits of some palm strung on it and a quantity of feathers at the end of long switches sticking out from the uppermost.

Panooda told us that these were all Coolcalagas or Mount Ernest people.

At the present time it appears that there are only two men besides Panooda's own family on the island; the mass of people are away in canoes, as indeed Teoma [Mrs. Thompson's native name] had previously told us were frequently the case.

What little we have seen unquestioningly justifies her opinion that the Coolcalagas are "very good blacks".

We have been waiting all day for Bramble . No boat ashore. Off to Darnley Id. morgen –dead beat all the way, wind being about E.

|

THE

HUXLEY

FILE

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||