Brierly Island, Louisiade Archipelago

June 16, 1849MacGillivray, Narrative I 223

I see I am getting out of my good habits but there has been nothing to write for the last few days. Various canoes have been to us every day, and the best understanding has been maintained. In some of the canoes they brought off some specimens of their ladies; they were ugly enough but not quite so bad as the Australians. They wear a girdle from which long grassy fibres depend as far as the knees so as to form a kind of petticoat. In this respect they exactly resemble the Darnley Islanders. They never stood up in the canoes as the men do but always kept sitting and sometimes shading themselves with a piece of matting.

One today had a child of which she took great care, shielding it from the sun with a light mat so that we could hardly get a sight of it.

Poor "Lighthouse" is lost. He strayed from the watering party yesterday and did not return. The jolly-boat was sent after him this morning but has not been successful. The ship's company, with whom he was a great favourite, are in despair.

We are unfortunate in our dogs, Lighthouse being the seventh or eighth that has disappeared since the ship was in commission. There is Denison's dog and Dayman's Billy and Pug and Native and another little beast of the skipper's, Brady's unfortunate kangaroo dog lost or as some opine shot at Cape Upstart, and Juno and the setter, left behind at Sydney this time.

That little skipper of ours is a greater ass than I thought. That he had neither smell nor hearing nor taste sufficiently refined to enable him to distinguish one sensation from another, sulphuretted hydrogen from Millefleurs, "God save the Queen" from "Old Dan Tucker", strawberries from mulberries–I knew long ago, but I now find that his eye is equally defective. The other day he and Brierly and I went across in the galley up the river, and each made a sketch of the same place. I finished mine in pencil and showed it him. He did me the honour ( ?) to approve, but said "Ah, wait till I get it out in colours". Thought I to myself we are going to have a Claude at least. The scene indeed was a beautiful one and a splendid subject, rich in colour and brilliant effects of light and shade. Last night the little man sent for me. I went and lo! the sketch, which with a look as much as to say "you don't see anything like that every day" he submitted to my inspection. I nearly burst out laughing. Words won't describe the absurdity of the thing. I was placed in a puzzling position, for I have a constitutional aversion to lying. So I said "Ah, exactly, sir. Yes, that's the Pandanus Tree and that's the water, and, ah, yes . . ." leaving him to form his own conclusions as to my opinion.

I am afraid his opinion of my taste is much diminished.

I have been so much occupied for the last two days that I have really not had time to make any notes in my Journal, notwithstanding the vast numbers of events I have to record.

On Wednesday morning the Captain determined to visit the small island (supposed to be Chaumont Id.) which the galley visited on the 2nd, in order if possible to open up a communication with the natives. We formed a formidable party, the 1st galley and second cutter with their crews, the Captain, Thomson, Brady, McGillivray, Heath, the sergeant of marines, James the Captain's servant and myself.

The galley conveyed the skipper and surgeon; the rest of us went in the cutter.

We got over the reef which fringes the island and nearing its southern shore we saw several natives running along the shore and gesticulating. We stood in towards them but as we neared they retreated among the cocoa-nut trees that thickly wood the hill side, their dusky shapes showing here and there as they peeped from between the trees. We might have landed here but the water shoaled away much and as the tide was falling the boats would have been hardly able to remain near enough to the shore to afford us efficient protection, so we stood off again and pulled round a point to the westward, opening a little sandy bay with a long spit running out from the bushes and allowing the boats to remain pretty close. There could not have been a better place for our purpose as from several canoes being hauled up on the beach it was clear the natives were living near and at the same time the long bare space, on which a sandpiper would have been a capital mark to anyone in the boats, quite secured us when landed against any treachery.

The Captain landed, giving directions to Dr Thomson to remain in the galley and cover him with his gun. Several blacks came down, but each party was rather suspicious of the other, the skipper with his usual want of savoir-faire looking as stupid as a stockfish, and the niggers not knowing precisely what we wanted to be about. After a while it occurred to me in my presumption that this was not the way to do any good, so I said "I don't know that there are any orders about staying in the boats" and holding up my coat tails waded ashore. I began to dance and the niggers began to dance, and then we sat down and began to draw some of them, and then some more of the officers came ashore and we were very good friends. They offered us yams and cocoa-nuts for "Kalouma" and we gave them red cotton night-caps, bits of glaring cotton handkerchiefs and other articles of virtù, with which they were evidently delighted. By this time there were some twenty niggers down on the beach. At some distance in the background three or four ladies made their appearance in their peculiar dress, looking just like ballet girls, a resemblance not a little increased by the jumps and springs they occasionally took, but the men waved them off and would not let them approach.

Everything seemed to me to be going on rightly, and so I quietly wandered away and espying a path followed it up and in twenty steps found myself in an open area containing three houses, invisible from the sea by reason of a screen of bushes and cocoa-nut trees.

All the natives were down with the boats so there was no one to be seen but a stray woman or two who ran off on my approach and I had an excellent opportunity for examining the houses. I got a pretty clear understanding of their build and then, knowing the skipper’s peculiar jealousy, I returned and told him that I could show him the houses if he would come quietly so as not to disturb the natives; so he and Brady and I went back, but when we came to the opening in the trees which led to the houses he turned back saying he thought it advisable to have somebody else with him.

Brady and I remained and he came presently with one of his boat’s crew and the sergeant (?) and some of the natives.

The little man had his book and pencil in his hand but to my certain knowledge he neither made note nor sketch, and seemed rather anxious to get away, wandering about in a regular fidget and seemingly unhappy till he got away. I notice these things because today he said to B– when he came on board, "Well, I have seen the houses and know all about them–got every particular". He seems to be much of Louis XIV’s opinion–"La France, c’est moi".

After remaining on the island for about an hour and a half and getting on very good terms with the natives, we departed, the blackies accompanying us off to our boats; we returned to the ship about two o’clock.

In the evening over the customary cigar the skipper says to the first lieutenant, "Well Suckling, we have had a very satisfactory communication with the natives today, so much so indeed that though I mean to send the cutter tomorrow to barter for yams, I don’t think it necessary to go myself. " "C’est moi" again.

So on the morning of the 5th, Thursday, the first cutter was manned, and Brady was dispatched with a supply of axes and knives to barter for the ship’s company, the Master going in charge of this party and Robinson as Mid of the boat, while McGillivray, the Surgeon, James and I went as idlers and supernumeraries.

We landed at the same place as before and this time the natives ran down prancing and gesticulating, as if to welcome us, in a far more friendly manner than before. Many of them had garlands of green leaves round their heads, knees and ankles, some had long streamers depending from their arms and ears and floating in the wind as they galloped along shaking their spears and prancing just as boys playing at horses do at school.

We soon were surrounded by them shouting "Kalooma, Kalooma", their word for iron, and offering us all sorts of things in exchange. One very fine athletic man, "Kai-oo-why-who-ah" by name, was perfectly mad to get an axe and very soon comprehended the arrangements that were made. Brady drew ten lines on the sand and laid an axe down by them, giving "Kai-oo-why-who-ah" who had hold of his arm to understand that when there was a "bahar" (yam) on every mark he should have the axe. He understood directly and bolted off as fast as he could run, soon returning with his hands full of yams which he deposited one by one on the appropriate lines, then fearful lest some of the others should cut him out of the axe, he caught hold of Brady by the arm and would not let him go until he got yams enough from the others to make up the number and the axe was given him. The yell of delight the blackie gave! He jumped up in the air, flourished it, passed it to his companions, tumbled down and kicked up his heels in the air, and finally catching hold of me we had a grand waltz with various poses plastiques for about a quarter of a mile.

I dare say he was unsophisticated enough to imagine that I was filled with sympathetic joy, but I was taking care all the while to direct his steps towards the village, which I wished to enter under Kai-oo-why-who-ah's respectable sanction. I think he smelt a rat, for he looked at me rather dubiously when I directed our steps towards the houses and wanted me to go back, but I was urgent and he gave way and we both entered the open space where we sat down and were joined by one or two others. I got him to sit for his portrait and we ate cocoa-nuts together and at last got on such good terms that he made me change names with him, calling himself "Tamoo", which I gave as my name, and giving me to understand that I was to be "Kai-oo-why-who-ah". When I called myself by the latter appelation and talked to him as "Tamoo" nothing could exceed their delight; they patted me and evidently said to one another "This is really a very intelligent white fellow". Like the Cape York natives they were immensely astonished at beholding one's naked legs, if one pulled up the trousers, spanning the calf with their hands and drawing in their breath and making big eyes. And once when my shirt was open and they saw the white skin of my chest, they set up a universal shout. I fancy that as they colour their faces black they imagined that we coloured ours white, and were surprised to see all our bodies of the same colour.

The women did not skurry away quite so fast as before except the very young ones; one old lady indeed passed from house to house upon her lawful occasions, but would not take any notice of me except by grinning when I held up some cotton print to her. They are not so hideous as the Australians, indeed, so far as I could judge at the distance, some of the young nymphs were comely enough. The old woman had a grass petticoat and a grass cape fitting round her neck and open at each side for the arms.

There were five or six houses, irregularly placed with clear spaces round them and at some distance, 30-40 yards, from one another. They were all of the same construction, about 30 feet long and fourteen high, supported by four stout posts about four feet above the ground, with a perfectly clear under space.

The posts are not more than twenty feet apart (in length) and some four-six feet distant (in breadth) so that the house which they support overlaps them on all sides. They are very stout and about 8-10 feet high, some 3 feet and a half from the ground, with an elliptical piece of wood like a shelf fitted on to them, and on the upper surface there were frequently roots laid out as if to dry; but these shelves must have had some other purpose, perhaps to keep animals–snakes, rats etc.–out. About six or seven inches above the shelf a strong stout cross-bar is lashed to the posts, forming the ends of a parallelogram whose sides are formed by two longer spars equally lashed to the posts above the cross-bars and supported by them. A third spar runs midway between these lateral ones and is lashed at each end to the cross-bar.

A number of thinner transverse bars are lashed across these again, immediately above them, and above these comes a layer of about a dozen longitudinal rafters; across these again is the proper floor formed of closely-set transverse narrow pieces, smooth on the surface and apparently split from some palm, so that the floor is formed of these layers besides the frame on which it is supported.

The roof is arched from side to side and rises in the middle to a height of 7-8 feet, but at the ends comes nearly down to the level of the floor; it is formed of a green thatch and outside this cocoa-nut leaves supported upon a frame of curved withes, like an Australian hut. The ends of the withes appear to be lashed to the cross-pieces.

As the fronts are 7-8 feet high and the floor not more than between four and five feet from the ground it follows that the upper ends of the posts stand out in the interior of the house, and a stout cross-piece is lashed to them and runs across as a sort of brace, supporting again at each end a longitudinal strengthening bar. These are all lashed together and to the withes of the roof. There are three other longitudinal spars similarly lashed to the withes, which run along, one in the centre of the roof and one on each side inside between the centre and the lateral bars before mentioned, so that altogether the roof is a very firm structure.

Several cross-bars run from one lateral strengthening bar to the others at distant intervals between the terminal ones. And the one half of their extent supports longitudinal sticks forming a sort of shelf, on which they keep root and chunam pots and other store matters.

A man may sit up but not stand in the interior of these huts. In one of the huts I saw the remains of a fire, but for the most part the fires with the cooking pots were on separate stages at some yards distance.

(The pots were of some kind of wood, and carved on the outside.) Not true–the pots are earthenware as I see by a fragment brought off to-day. How they contrive to make them of the size (18 inches across) I don't know.–July 31.

Behind the houses on one side they had formed a very curious inclosure, on the face of the hill. It must have been about 3/4 acre in extent, but had not been cleared or apparently touched with any agricultural instrument, nor was anything, e.g. yams or the like, to be seen growing therein. The fence surrounding it was some 3 ft high and very strong, being formed of a double row of stakes, each pair being 18 inches apart. Each pair of stakes held the ends of a series of strong wooden bars one above the other and as the stakes were strongly lashed the whole formed a very strong fence. In one corner of the inclosure there was a sort of little shed of dry withered cocoa-nut leaves but it appeared to cover nothing.

As it is quite certain from what we saw in another part of the island that they don't take the trouble to enclose their yam and banana ground in this manner we imagined that the fence was for the purpose of keeping pigs. I walked all round it but could see nothing but trees; here and there were marks of grutting up. As I walked I could hear the women cutting about among the bushes near me, but of course I took no notice but quietly pursued my walk.

When some seventeen or eighteen hatchets had been disposed of–more yams being obtained for the later than the earlier ones–we had about 360 pounds of yams in the boat besides private supplies, and we shoved off, leaving our friends in the best of humours. We were no sooner away than we saw three or four women come capering down, with leaps that would have done honour to Taglioni.

We pulled round the point to the south side of the island and there all the officers except the Master landed.

This side of the island is very steep and is covered with cocoa-nut trees; at the top it is almost bare of trees but is clothed with the long luxuriant grass in which all the islands we have seen abound. From the boat we could see one patch of about half an acre covered with bananas, some of which were to be seen elsewhere, so that we concluded that this must be a cultivated spot. Anxious to ascertain if this were really the case, Brady and I ascended the hill, and found that this was in truth a rough sort of garden, not fenced in in any way but cleared of grass and of trees, the young slender trees being all cut down to within three feet of the ground. There were a great many yams which appeared to have been planted near these stumps so as to climb up them like so many hop plants.

There were a great many bananas, all young and without fruit, and these like the yams were planted quite irregularly. On returning to the beach I found that the natives had come round the point and from all I could hear I suppose that they must have imagined that we were taking French leave with their cocoa-nuts and yams. One of them who was in advance appeared very angry and scowling and poising his spear made up to Robinson. Robinson took it very coolly, just bringing his gun to his hand in readiness and looking at the fellow, who on coming closer thought better of it. As it was, it was as well there was no firing, though had I been in Robinson's place I should most undoubtedly have shot the man. I don't see the fun of waiting till you have a spear through you before you fire.

However, when they saw that we had been doing no mischief and were quite strong enough to take care of ourselves, they became very friendly again and bartered a few more cocoanuts etc.

Kai-oo-why-who-ah and one or two more were very desirous to understand the use of our guns and so James took aim at a swallow flying overhead and brought him down beautifully. Our friends were extremely astonished both at the report and the result, and at first would not so much as go near the bird, but when it was picked up and shown to them they seemed still more surprised to see the blood.

Some more shooting went on, rather unwisely as I thought, for the shots were not by any means successful, and then we parted, excellent friends. We hauled off for some distance from the shore to dine and the natives remained on the point looking at us.

We amused ourselves by firing at the bottles that were thrown overboard, taking care to fire in the opposite direction to the niggers. But the sergeant like a fool discharged his musket, not exactly at them, but sufficiently towards them to frighten them round the point. What should we have done had one of them thrown a spear within twenty yards of the boat?

|  |

Hut on Stilts |

Darnley Island HutHut with Sleeping Resident |

| MacGillivray, Narrative I 224-225 | |

Brumer Is.

This Brumer Is. is one of the most beautiful we have seen, remarkable at once for its singular form, its greenness and the immense number of cocoa-nut trees; they literally crown the island. The upper regions are free from trees here and there, and with a glass we can see hurdled inclosures apparently for the cultivation of yams etc.

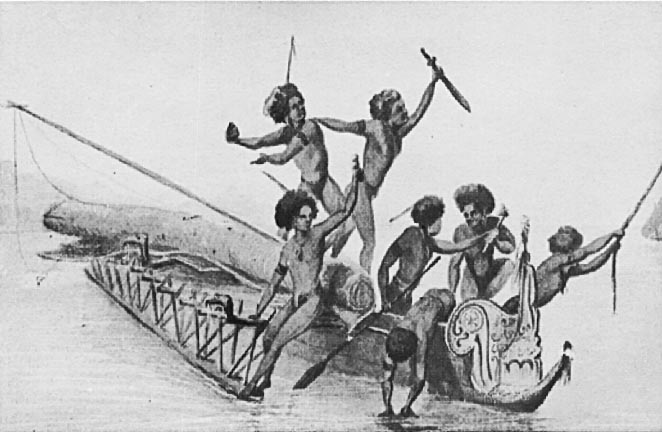

The natives have been off to us today in considerable numbers although it has been blowing hard with occasional sharp squalls. Only one set came in a canoe and this differed from those we have seen before in having no raised gunwale and in the outrigger pole being more horizontal. We saw no mast or sails. The paddles are longer (over six feet), more slender and far better made than any we have seen yet. They are of some hard but light wood, and the head of the slender handle is very neatly carved.

The most of the natives came off in catamarans composed of three or four logs (usually three) lashed together by cords of rattan which though doubtless strong appeared very slight. These catamarans varied much in size, from nine to 30 feet long and bearing one to a dozen men. That they are permanent constructions and of common use appears from the elaborate carving bestowed upon the pointed ends of the middle logs–the outer logs are shorter than the middle one and though not carved are smooth and pointed at each end.

It is amusing to watch the careful dexterous manner in which the natives balance themselves on their queer-looking structures over which the sea continually washes, and how they prevent their cocoa-nuts and yams from washing off, or dive after any stray part of their cargo.

They resemble the other Louisiadians perfectly in appearance, but do not understand the words we have elsewhere collected, nor do they use the same word for iron etc. They have some ludicrous signs which appear to be meant for symbols of friendship and whose repetition by us produced extravagant signs of delight and amusement among them.

This afternoon one fellow who appeared to be a great wag–perhaps the intense blackening of his face might be a sign of his being a wit–having obtained a tin-pot, began to make use of it as a drum, putting it under his left arm and tapping on the bottom or lid as the case might be with the fingers of his disengaged hand. He had three white cowries in a necklace, and he prepared himself for his performance by putting the string of his necklace in his mouth so as to have the shells in strong contrast with his black face.

To show them that we could do a little in this way too, the skipper ordered the drummer into the chains and marvellous was their amazement when he beat off a roll. They seemed a little frightened at first, particularly as the whole ship's company, attracted by the noise, rushed to the side and shrouds to see what was going on, but soon recovering. The "wag" appeared to be intensely delighted. In the meantime the fiddler and fife had joined the drummer and the two struck up a lively tune.

The wag was like to go out of his senses, prancing about on his unstable foundation, listening to catch the time and putting in a touch of his own drum here and there. We were all convulsed with laughter. Even when it was time to be off, the wag would take his paddle and work away vehemently for a moment or two, then the music became too much for his feelings and he would start up, drop his paddle and drum; then paddle again and drum again until the drumming was over.

Sunday.

Today at one o'clock the first and second cutters were despatched ashore under Simpson's orders to enter into communication with the natives and ascertain if possible whether water was to be obtained. Several of the natives (among them the "wag" or "dancing master", for he delights in both soubriquets) had been on board and we persuaded the "wag" and another without difficulty to accompany us. They seemed indeed rather delighted at being transported ashore like gentlemen, and examined very curiously the different parts of the boat. She had been up for some time and consequently took in a good deal of water, whereupon the wag fished out the balers and set to work in right earnest to clean the well. As usual, however, with savages he soon tired of his work.

A nasty little reef of rocks runs along the beach at a short distance, and we got well ducked in going ashore. A number of natives, both men and women, had come down to the beach and seated themselves on the centre piece of a large catamaran hauled up there. As we landed, the women withdrew to a little distance but the men advanced and taking hold of our hands and making their ordinary remarkable signs of friendship, led us to the log, where we all sat down for a short time.

They then proposed that we should go to their village, and as they had no arms, and we were a strong party (Simpson, Thomson, Brady, McGillivray and myself) we saw no difficulty in accepting their invitation. A special friend or chum attached himself to each of us and we marched up the steep and craggy path which leads over the lowest part of the central ridge of the island, hand in hand. The view from the top of the ridge is lovely in the extreme. Right before you is the wide ocean with a tremendous line of rollers as it breaks over the rocky shallows near the beach. At your feet in a valley between high precipitous hills on each side is a clear level space, thickly planted with cocoa-nut trees, and peeping among these lie the curious gables of the native houses. Descending by a very picturesque but somewhat inconvenient path we soon reached the village where we found all the feminine population and a good share of the masculine up in arms to receive us. They got out their drums and raised the most hideous uproar imaginable on our arrival. We were soon great friends, and I went prying about to examine the houses. They are raised on posts in just the same fashion as those at Chaumont Id., and the general structure is much the same, but their shape is very different inasmuch as the roof is raised at each end into two very high triangular gables, its ridge sweeping into a concave curve. The gables are formed by two long poles lashed together, the space left between them below being filled by a sort of thin wall made of flattened cane or some such material. The floor does not come out so far on the gable nor does the thin wall of the gable reach down to the level of the floor so that there is a sort of door lift, which is reached by a wooden stair, or rather step, of the simplest construction such as we saw at Chaumont Id.

Besides looking at the houses I obtained one or two sketches of the women who, though diminutive (as indeed both men and women are), are by no means so bad looking, and by that time Simpson wanted to be off again, and we marched back attended by the whole population of the village.

We had made them a great many presents both on board the ship and during our visit to the village, and on our return to the beach, in order as I suppose not to be outdone in generosity, each of our chums went and cut a lot of cocoa-nuts, which were speedily deposited in the boats without the donors accepting any further payment for them.

More than this, the second cutter's anchor had somehow or other become foul and two natives seeing what was the matter pushed off in a catamaran. On reaching the boat one of the two, an old man, dived down and after three or four attempts (during each of which he remained under water for what seemed to all of us a most astonishing time) succeeded in clearing it. He was going away without asking for anything but we called him back and gave him an axe.

We were all so pleased with the primitive simplicity and kind-heartedness of these people that we gave them three cheers on our departure, a proceeding which astonished them not a little.

During our whole visit we saw no arms of any kind in the hands of any of the males.

August 20, 1849

Our yesterday's visit had been so successful that the Captain determined on going himself this morning, with the purser, to visit the village and barter for yams etc. However just before starting he changed his mind and sent Simpson in his stead. As the boats approached the shore we saw no signs of any such numerous assemblage of men as yesterday. There were but a few women, and one or two young men and boys, sitting down, who retreated up the narrow path on our landing. The young men and boys came down to us and "fraternized". But as no others made their appearance we proposed to our friends to visit the village, to which they made no manner of objection. So we, i.e. Simpson, Brierly, McGillivray, and myself, marched off leaving Brady and the Captain's steward behind with their wares until we should return with some customers. We halted for a while on the top of the ridge to get some sketches and then proceeded to the village where we found nobody to receive us but a parcel of women with our friend the "dandy", looking at once friendly and martial, the former feeling being expressed in his countenance and gesture, the latter by means of a large wooden sword, with which on his shoulder he strutted about. He had a young girl on each arm, one of them my friend of the previous day, and these he gave us to understand were his wives.

Although very civil, however, he was evidently not at his ease, and seeing this we did not stop, but turned to go back, expounding to them by signs that we had plenty of "lopoo-roopa" and other grand things if they would come with us. Our determination to return, too, was somewhat excited by certain distant shoutings we heard in the brush as though people were hastening towards us. The Dandy and his feminine train accompanied us on our way back, keeping last between us and the ladies, and as we went he explained to me some very long story in a private and confidential manner. What it might mean of course I can't pretend to say but it appeared to be something to this effect. "Really my dear friend, I am very sorry to be obliged to treat you in this inhospitable manner, but you can see, our acquaintance is so very slight, and ladies are so unprotected here, that the other gentlemen would be angry if they found you here."

I had given him an axe-head for old acquaintance sake, and when we arrived at the beach, he and one of his wifes took a different direction to the rest, beckoning to me to follow. I went and we came at length to a group of cocoa-nut trees. He went up one of them, while I staid below and sketched his wife. She took care to keep a very respectable distance between us, hardly allowing me to put her in proper position. After a while the Dandy descended with a bunch of green cocoa-nuts which he explained were for me and then (I regret to state it) gave them to his wife to carry down to the boats for me.

When we arrived at the boats there was a great noise and confusion. Some strangers had arrived and were by no means so well behaved as the islanders themselves. In the midst of the noise I sat down on a log and began to draw the Dandy's other wife (who had come to ask me to do so) a reddish-brown-haired girl with the hair in thrums and by no means so good looking as the other. I had almost completed my sketch, when I heard Simpson call me and saw that all our folks were retreating to the boats. I thought there was going to be some row and walked into the cutter with very short leave-taking of my friends. When we had shoved off I managed to make out that there had been some snatching at the barter articles, that the women had been observed bringing down axes with which the men provided themselves, and that one fellow, so far from fraternizing when Brierly made the usual signs, spit over his shoulder with a very contemptuous gesture. That so far as I can collect was the sum and substance of what happened.

Today and yesterday we have had a great number of canoes and catamarans alongside, making no small noise. In fact their visits have become so troublesome that none are admitted on board, greatly to the disgust of the Dancing Master who did not at first at all understand the prohibition. Today four or five of the women came off in a canoe, among them the two wives of the Dancing Master, but no persuasion or temptation would induce them to come up. They had some men with them when they came and these did the paddling for the most part, but going back again when they were half way over to the Island, the men jumped into a passing catamaran, leaving the poor women to stem the current as they best might, and a long time it was before they reached the shore.

A very large canoe came to us from the New Guinea side, the largest that has been seen. It had a large oval sail like the Rossel Id. canoes, and a crew of 27 stout natives. We gave them a rope over the stern, by which they held on while a fine venerable old man who appeared to be a sort of chief, embarked on board one of the small canoes and came to us. I spoke to the first lieutenant and got him on board, when we showed him over the ship and made him some presents. Old Suckling was horrified when the old fellow offered to rub noses –imagining he was going to kiss him. The old man was not unlike the Bishop of Norwich, only taller. By dint of dogging him about and getting a line here and a line there I contrived to get a likeness of him.

The natives here have a great variety of vegetable products –cocoa-nuts, bananas, guavas (unripe), breadfruit (unripe), yams, sweet potatoes, cocos, betelnut and betel pepper leaf, and for some days past they have brought off large hanks of very strong flax with a very long fibre (6-9 feet in length).

They must have a considerable mechanical turn, for besides their carving, and the careful way in which the large beams of the catamarans are adzed flat on their upper surface, they make admirable ropes. And they have several varieties of musical instruments–drums of various sizes, hollow bamboos through which they roar and bellow, pans-pipes of seven reeds, and a kind of large Jew's harp.

The people seem happy, the means of subsistence are abundant, the air warm and balmy, they are untroubled with "the malady of thought", and so far as I see civilization as we call it would be rather a curse than a blessing to them. I could little admire the mistaken goodness of the "Stigginses" of Exeter Hall, who would send missionaries to these men to tell them that they will all infallibly be damned.

The niggers have been having a grand corobbory ashore tonight, lights have been dancing and winding among the trees and their drums have been heard. Not to be outdone we burnt a blue light and sent up two or three rockets, which must have astonished them considerably if they saw them. I know nothing that has so strange a ghostly spectral look as a ship lighted up by a blue light.

|

|

Spears, Shield, Basket, Comb |

Papuan Pipe with Bamboo Tubes |

| MacGillivray, Narrative I 279 | MacGillilvray, Narrative I 282 |

The usual crowd of natives and canoes from all quarters. In consequence of some cheating that has been going on by some of the ship's company, orders were given this morning that none but the officers and their servants and a man from each mess should be allowed to barter. It is a very good thing that this regulation has been made, for the natives have been imposed upon in the most shameful manner. For instance, one of our people would hold up a fine piece of iron and make signs that he would give it for certain yams etc. The native hands up his yams unsuspectingly, and "Honest Jack", shoving a piece of worthless tin into his hand, walks off leaving the native to express his astonishment and disgust as he thinks fit.

It must be confessed however that the natives paid the sailors in kind occasionally, getting the "loporopo" beforehand, and then looking up with a vacant stare into the face of the expectant Jack, who all indignant at the cheat was probably pouring forth torrents of choice Billingsgate. This would happen occasionally, but it was by no means the rule and I do not know that any of our islanders have been guilty of such dishonesty.

The canoes had left us for the greater part of the afternoon, but about half-past four I heard a great noise on deck and going up found it to proceed from a canoe coming off from the island with an old woman, a boy, four or five men and a fine live pig securely lashed and slung over a pole after the manner of the Pig Island porker. The old woman was dancing, shouting and flourishing an axe in the most frantic manner upon the outrigger. And the sternmost man was winding forth the most dolourous noises upon a large shell, while the others added to the concert by shouting and yelling at the top of their voices. Directly I espied "ye pigge" I sent for two axes and exhibited them, whereupon our friends paddled up alongside in double quick time and handed up the porker, not before one native, however, had taken his spear and, making a grand flourish, stuck it into piggy, transfixing the unfortunate brute so that we were obliged to kill him forthwith.

The captain had in the meantime come on deck and he ordered one of the natives (the transfixer and chief man to all appearance) to be admitted. When he came on deck he had in his hand a wooden sword, and he immediately commenced a long oration, first casting the sword on the deck, then making signs to us to go ashore and finally going through the motions of sticking himself or being stuck with a spear. These motions and the energy with which he performed his part attracted a good deal of attention and some very marvellous theories were raised to explain them. The most elaborate hypothesis maintained by the orthodox was this. The other tribes, jealous of our favouring them, had been ashore, insulted the women and speared the pigs; a general row had ensued and the invaders been beaten (according to some–according to others it was a drawn battle) and the present visit was to be considered as an ambassadorial message (the old woman being probably minister plenipotentiary) propitiating us with a pig and demanding our aid. And furthermore Dayman averred that in his belief it was all connected with the row with the boats.

For my own part, I am as usual inclined to put a rationalistic explanation upon the mystery. To my mind the killing a pig among these people is considered a great occasion, a sort of grand feast in their church. They therefore brought this off with all ceremony and finally wish to inform us that if we will go ashore like jolly fellows, they will kill one for us, and have a grand corobbory. There is nothing I should like better.

After a while a large catamaran came from the shore, but as she was pulling up, the canoe filled by being caught on the side steps as the ship rolled. She did not sink, however, and the old lady kept her seat with the utmost coolness, canoe and all drifting down with the current. The large catamaran (on board which was our friend the Dandy) went to the canoe's assistance and we gave the end of the deep-sea lead line to a small catamaran alongside with directions to carry it to their companions in order that they might not drift out to sea while righting their canoe. The large catamaran and canoe must have been a good quarter of a mile away by the time the line reached them. They immediately made fast and made signs to us that they had done so, when we got the line over the winch and wound them up.

They were greatly pleased at this bit of assistance and the old woman was persuaded to come on board at last when she saw the Dandy and others so well received. The Dandy as usual brought a present for the Doctor in the shape of an uncooked yam.

The old lady was rather nervous, but became considerably reassured by our respectful treatment and the presents she received on all hands. Going away they were greatly delighted at getting possession of a cask of damaged flour, several of which were being thrown overboard. They seemed perfectly to understand its use, making some into a paste with a little sea water in order to show us what they would do with it.

Yesterday afternoon catamarans and some canoes from the island came alongside. The natives brought four or five of their women with them and these were without very much difficulty persuaded to come up. We did the honours and dressed the ladies up to their infinite satisfaction. Afterwards two of the men got their own native drums (wh. we had on board) and performed a dance for our amusement. A very singular affair the dance is too, consisting of a series of not ungraceful leaps and jumps, in a sort of cat-like manner, the body bent, the chin raised high up, and a sort of absurd half-humourous half-conceited expression on the countenance. The steps are accompanied in most accurate time by taps with the hand upon the drum, and the dance is always concluded with several short taps one after the other. Occasionally the two performers poussetted together up in a corner but for the most part they leapt along the length of the quarter deck and back again.

The girls were very merry and unconstrained though perfectly modest in their behaviour. They seemed half inclined to have a dance too but had not the courage. It amused me very much to see how perfectly women are women all the world over. There was the same incessant flow of small talk among themselves, the same caressing and putting their arms round one another, as would have been seen in any other group of women in any other place from London to Sydney. And to complete the resemblance they all persisted in kissing and hugging an impudent young varlet of a ship's boy who went down on the catamaran as they were going away. One of these damsels, who had disfigured her face by a copious coat of black pigment, was more affectionate than any of the others and seemed to take a most roguish delight in inspecting the traces of her kindness, left very visible upon the boy's white face.

One of the dancers (the same man who came off with the pig) very unceremoniously gave us to understand that he meant to stay on board by composing himself into a slumbering attitude upon the deck. By first grunting and going through the motion of sticking himself, and then howling, and pretending to hit something very vehemently over the head, he gave us to understand that if we would go ashore he would have a pig and a dog (!) killed for us, accompanying these assurances with many declarations about plenty of "quatai" or yams. He made up his mind that we would go ashore in the evening and have a jolly corobbory but he was wofully disappointed, for manifold as were the hints the skipper received he neither went himself nor offered to let anybody else go.

In the evening however he got up some amusement for the native by showing him his magic lantern. The chromatic colours and some of the strange apparitions of men swallowing rats etc. produced great exclamations from our savage friend, "dem! dem!" Afterwards he was taken up on the poop and a rocket fired, which astonished him still more. He was dressed up in a complete suit of coat, shirt and trousers, and hat. He seemed very temperate, would not touch our grog or wine and water, and preferred drinking his water out of one of their own vessels rather than from a tumbler.

We made him up a bed under the half deck but he found that too hot and went on to the poop, where he went to sleep in the midst of hot discussion that was going on among a party of us.

About half-past two in the morning he woke up and immediately began walking about and singing in no very low tones. He had to be informed that this was not quite comme il faut but gave the usual "ben! ben!" to all hints that he had better compose himself again.

The next morning (Sunday) he was very anxious to go ashore and that we should come with him, but the skipper for some reason or no reason did not choose to lower a boat and so the poor blackfellow remained, his spirits gradually ebbing in spite of all we could do to cheer him, till at last in the afternoon the poor fellow was fairly crying.

As no canoes came or appeared likely to come the Captain at last late in the afternoon sent him ashore in the cutter. He was well loaded with presents of various descriptions.

|

THE

HUXLEY

FILE

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||